Maintaining a Duolingo streak has been much easier since the pandemic, and more recently our move. On the other hand, we haven’t been able to visit Japan since 2018 (finally got a refund for a May 2020 trip deep into 2021), so while it’s easier for me to study, I haven’t had a chance to use what I’ve been learning.

(NO Diamine Invent 2022 spoilers in this post, be assured.) I bought the Diamine Inkvent calendar for the first time this year, and I decided NOT to wait until December to open it up. Like a lot of people, I’ll be traveling for a few days that month, I know I’ll have a ton of work on my plate, and there are no kids in the house. Instead, I’ve been allowing myself to open a bottle a night–in order, I’m not a complete monster!–as a kind of reward when a) I get “enough” work done on my book, and b) I generally have time to enjoy the opening process. I honestly don’t know if it’s much of a motivator–it’s an impending deadline that keeps me sat at my desk for hours, not the prospect of ripping the plastic seal off a little bottle of ink–but it sure is fun. So, my question to the world (or maybe to Diamine): Why wait for December and “advent”? If Diamine, or anyone else except Noodler’s, put out 31 mini bottles of ink in some kind of mystery packaging, I’d gladly buy it and use it as a reward to myself for good behavior at any point in the year. No need to come up with new formulations–that does seem like a LOT of work–just surprise me! 🖋

🎙️For this week’s episode of Slate’s Working podcast, I got to ask lesbian romance novelist Harper Bliss how she writes three books a year (and shoots for four). That feels like an unbelievable level of creativite output to me–though she’d like to write more! We also talked about writing books in series, self-publishing, and being a neurodivergent author.

This statue (or is it a sculpture?) in the Water of Leith is almost too realistic. When we first got here, he was wearing a T-shirt. 📸

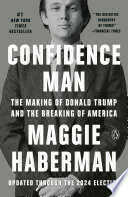

I’m listening to Confidence Man📚, read in a defiantly flat narrative style by author Maggie Haberman. Even more than other accounts of the Trump presidency–and I’ve read a few–it’s a shocking reminder of just how many outrages were committed by the 45th president. When the book came out, there was lots of discussion about whether it was kosher for Haberman to hold back some revelations for the book rather than reporting them as she learned them in the New York Times, which employs her, since they could have changed the changed the way some people voted. (My take: Apart from any considerations of news value, it’s part of the informal contract with your employer that if something happens on your beat while you’re employed by a newspaper, you have to write about it–or share that information with a colleague who’ll write about it. Presumably, Haberman and all these other journalist-authors make agreements with their Times editors when they sign book contracts.)

Three-quarters into the book, that question feels like a barely relevant abstraction. Nothing that was held back by Haberman or by any of the other journalists whose books about Trump I’ve read would’ve made the slightest bit of difference to the outcome of the 2020 election. There were so many affronts to decency reported on and covered extensively every single day of the administration that if you believe in the rule of law and the institutions of government, there really shouldn’t have been a moment’s doubt about whether Trump was suitable for office.

As I mentioned before, Haberman doesn’t bring much variety to her narration. At first that bugged me a bit, but it’s perfect for a book with a lot of quotations from Trump. Absent his blustery style of speech, Trump’s words reveal the emptiness where empathy and consideration for others should be.

As it does every Nov. 11 at 11 a.m., Britain just observed the two-minute silence that commemorates the Armistice that ended World War I. I was almost sad to be at home and “naturally” quiet rather than conducting a conversation, because while the silence is an opportunity to inwardly reflect rather than to publicly signal one’s feelings about war and man’s inhumanity to man, it feels more powerful to be part of a sudden hush.

I once happened to be in Israel on Yom HaShoah, the Holocaust Martyrs and Heroes Remembrance Day, when a siren sounds and everything stops for two minutes. It’s not simply a silence, but a cessation of all activity. Where I was at least, drivers stopped their cars, businesses paused all activity, and everyone stood and contemplated history. It was disruptive in all the right ways–a reminder of the importance of the event.

- 1

- 2